A Plane for the Common Volks |

Designed by Hobby Sorrell, these original plans are for serial number 176. Great vintage plans for a home-builder. Can be powered by any engine over 18 h.p. Plans call for a OMC Cushman 4 cycle boat engine. Volksplane II original article on proto-type aircraft. (Four pages, including side and top view with pictures. As a member benefit, you can obtain a copy of an EAA-published magazine article listed above, free of charge, by calling EAA Membership Services at 1-800-564-6322.

I'm a firm believer that anything that flies, no matter how simple, is far more complicated to build than it would appear, but with the Volksplane, even if it's twice as complicated as it looks, it's still down on a coloring book level. I can almost believe the line in the Evans brochure that says the airplane can be built in six to nine months of spare time. That makes it the ideal airplane for the impatient pilot. (I think I have next winter's project figured out.) Just think how fast two or three guys could put one together. Of course, when things are sacrificed for simplicity and safety, something has to give, and in the Volksplanes, the first thing that simplicity threw out the window was aesthetics. Safety took care of blazing performance. When the energy source that keeps you in the air may be pumping out as little as 40 horsepower, you don't have much choice but to use a lot of wing (unless you want to fly like a clump of grass). In the VP-I, that means 24 feet of span (27 in the VP-II). That much wing gives leisurely takeoffs and landings, but it adds extra drag to the copious amount generated by the rest of the airplane to keep cruise down around 75 to 80 mph. The long wings don't make for a snappy airshow roll rate either. But, it flies. It really flies, and although the conditions under which I flew the VP-II were less than favorable, it performed at least as well as many store-bought planes would have. As I' prepared to hop in, I took careful note of how far my posterior protruded so I wouldn't get it caught in the already spinning prop while I was boarding from the leading edge of the wing. Then I told Beatty to exhale to make shoehorning me in a little easier. One thing to remember when wedging yourself into a VP-II is to prearrange who is going to have both arms inside. Beatty and I forgot until we were ready to take off, and he had to handle the brakes and throttle because my left arm was outside frantically clutching at his jacket. I wish now that I had been able to fly a VPI with the same 2000cc engine because I'll bet it's an entirely different animal on takeoff. With us two heavyweights aboard, the VP-II didn't exactly surge forward and claw its way into the air, but it did a whole lot better than I expected. The takeoff roll was on the long side, but we were up and away at close to 400 fpm, which isn't bad. The first thought that ran through my mind as I felt the gear scrub clear of the pavement was, 'Rub-a-dubdub, two men in a tub,' because I felt positively naked. The feeling of being 'on' rather than 'in' the airplane is incredible. The whole machine seems far below you, almost out of your field of vision. Even while sitting on the runway, the airplane hardly penetrates your peripheral vision. What had been an extremely shallow ground angle (9 degrees versus 15 to 20 degrees for most taildraggers) felt slightly nose down in the air. I was amazed that nobody had told the Volksplane it wasn't a transport aircraft, because that's how stable it felt in cruise. As a matter of fact, it's a little too stable for me. Bash the stick in any direction and the machine begrudgingly gives up level flight and heads in the direction the stick was pushed, but it returns to the straight and narrow almost immediately. Part of this don't-push-me attitude comes from ailerons that are disappointingly heavy and slow. Acd systems canvas professional edition 9 for mac torrent. Part of that is due to system friction, but the rest is because the surfaces are just too big—and Evans admits it. He didn't want to have to incorporate a false spar to hang the ailerons from, so he ran them clear into the rear spar, something close to 30 percent of the chord. He told me that anything over about 20 percent is wasted, so he evidently is thinking about rebalancing and lightening up the aileron loads. For an airplane that appears to set aeronautical engineering back 70 years, the tail group is strangely modern. All surfaces are single-piece stabilator/ruddervator types. Because these kinds of surfaces give very little feedback to the pilot, they have to be fitted with anti-servo tabs to keep them from being too light. Evans and crew did a fantastic job of designing what could have been a very cantankerous type of tail group. It seems to be balanced nearly perfectly and no matter how you fly it, it feels like a normal tail. There isn't even much change of effectiveness at slow speeds, which might be expected. Personally, I expected all the ragged air that was ripping around our heads and shoulders to be raising all sorts of grief with the rudder, but if it was, I couldn't feel it. Volksplane stalls can't be described, because there aren't any. None of any consequence, anyway. All that happens with the stick in your lap, regardless of attitude, is a little shuddering, and maybe at around 45 mph it will try to stall a little and one wing will drop slowly. Relax pressure, add power, and you're on your way. Once you've taken off, turned and stalled it, there isn't much left to do in a loaded VP-II but aim it at some distant point and go chugging off on a cross-country. I can't say that I'm wild about the tourist-class accommodations of the VP-II, but flown solo it would be incredibly roomy. Evans doesn't claim his plywood beetle bomb is a normal two-place airplane, but rather says it's 'an occasional two-place airplane. It's primarily to take a friend (a good friend) along for a ride.' However tight the seating, Evans says he and his Convair engineer friends have gone on dual cross-countries as far away as Tucson—300 long, but cozy, miles away. I was absolutely positive what it was going to be like to land: very easy. And except for one minor problem, it is. I'd almost be willing to bet that somebody who had just been checked out in taildraggers would do a better job of landing it than a pilot like me who spends all his time in taildraggers. We're so used to pulling into a much steeper ground angle during the flare, for a full-stall landing, that we invariably land Volksplanes tailwheel first, with the mains a foot or two in the air. Quarterflash best rar for mac torrent. Because the ground angle is so flat, the airplane can't be full stalled without that kind of embarrassing arrival. It is flown on in a nice flat attitude, which assures that a neophyte isn't going to stall out a couple of feet up. I'd say the best testimony as to how easy the VP is to fly is the often-repeated story about the VP-I builder at a North Carolina fly-in who set a record of sorts by checking out 34 different pilots in his single-place bird in only a day and a half. There were no problems at all, and everybody thought he was nuts (or extremely confident of his airplane). There are going to be a lot of people who just can't see the purpose of something like a Volksplane. It can't go busting into TCAs, while squawking 'ident' at the top of its voice, and with a maximum cruise speed of 95 mph (75 mph being more economical), a long cross-country is anything over 50 miles. But the Volksplane definitely has its place. It belongs right beside the Cubs and Champs that bring fun into the lives of weary space-age pilots. It's cheap, easy fun—less than $1,500. And in an age when men in dirty raincoats approach you on street corners to sell you a single gallon of gas, you can go chortling around the skies on something less than 3 gallons an hour, getting a minimum of 25 miles to the gallon. But all in all, the most enchanting thing about the boxy Volksplanes is that even the average, all-thumbs backyard clod can see the end of the project before he even begins. He can look at the plans and easily see that it won't be three years until he can enjoy the fruits of his long nights in the basement. It might not be the six or nine months Evans advertises, but it's certainly not going to take forever. That's the charm of the Volksplane—it's not going to be the work of a lifetime, but it's bound to provide a lifetime of pleasures. BD Empty weight .......... 640 lbs |

| VP-1 Volksplane | |

|---|---|

| Evans VP-1 Volksplane at Pima Air and Space Museum | |

| Role | homebuilt light monoplane |

| Manufacturer | Homebuilt |

| Designer | William Samuel Evans |

| First flight | September 1968 |

| Produced | over 6,000 sets of plans have been sold |

| Unit cost | |

The Evans VP-1 Volksplane is an American designed aircraft for amateur construction.[1] The aircraft was designed by former Convair, Ryan Aircraft and General Dynamics aeronautical engineer William Samuel Evans of La Jolla, California.[2]

Design and development[edit]

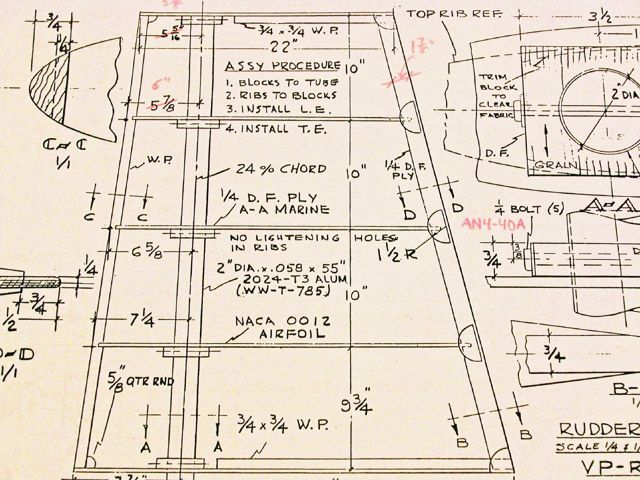

In 1966, Evans began engineering work on the VP-1, choosing an all-wood, strut-braced open-cockpit single-seat low-wing design for ease in amateur construction.[3] Designed to be simple to build and safe to fly, performance and appearance is of secondary importance.[4] To make construction simple, marine grade plywood is used for the slab-sided fuselage structure. The wings are designed to be detachable to allow the aircraft to transported by road.[5]

The VP-1 was designed specifically to utilize a modified VW Type 1 automotive engine from the VW Beetle.[6] The fuselage is built in a warren truss arrangement where the exterior plywood takes the diagonal stress loads, therefore eliminating the diagonal members to maintain simplicity. The vertical and upright members are staggered to keep the joints as simple as possible. The wing is of a forward and aft blank spar design which uses stack-cut plywood ribs of equal size in order to keep construction time down. The ailerons are hinged directly behind the aft spar. For simplicity no flaps are provided. The wings and tail surfaces are fabric covered.[7]

Because the design lacks aerodynamic refinement, the Volksplane requires more power than most aircraft its weight to fly. Some builders have altered the fuselage design to improve the aerodynamics and aesthetics.[4][5]

The design was developed into a two-seat version, the Evans VP-2, with an enlarged cockpit although this variant is no longer being offered.[8]

Operational history[edit]

The Volksplane first flew in September 1968.[3] Offered as a set of plans, and marketed as a 'fun' aircraft, the Volksplane was immediately popular with home builders who saw it as an inexpensive and easy-to build project. A number of examples have been built with variations in the design. In 1973, Mohog, a mahogany-skinned Volksplane, with further modifications to the basic design incorporating monocoque wings, strengthened roll bar and a blown bubble canopy, was built by the Wosika family of El Cajon, California, at a cost of $3,000.[9]

Construction of the Volksplane is relatively straightforward, and, according to some home builders, almost like building a 'giant model aircraft'.[10] Flying characteristics are relatively benign, as the intent was to create a simple, and easy-to-fly aircraft. Although not intended to be an aerobatic design, gentle 'aileron rolls, lazy eights, wingovers, chandelles and steep stalls' have been conducted. A total of approximately 6,000 plans have been sold to date.[11]

Variants[edit]

- Evans VP-1

- Single-seat homebuilt[4][5]

- Evans VP-2

- Two-seat homebuilt

Specifications (VP-1 – 40 hp engine)[edit]

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1982–83[12]

General characteristics

- Crew: one

- Length: 18 ft 0 in (5.49 m)

- Wingspan: 24 ft 0 in (7.32 m)

- Height: 5 ft 1½ in (1.56 m)

- Wing area: 100 ft² (9.29 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 4412

- Empty weight: 440 lb (200 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 750 lb (340 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Volkswagen air-cooled flat-four, 40 hp (30 kW)

Performance

- Never exceed speed: 120 mph (104 knots, 193 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 75 mph (65 knots, 121 km/h)

- Stall speed: 40 mph (35 knots, 65 km/h)

- Rate of climb: 400 ft/min (2.0 m/s)

See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Evans VP-1. |

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Hook, Thom. 'All those planes you can build from plans.' Popular Science, June 1970, p. 99.

- ^Purdy 1998, p. 152.

- ^ ab'Evans VP-1 Volksplane history.'Evans Aircraft Company, 2017. Retrieved: August 29, 2017.

- ^ abcBayerl et al. 2011, p. 101.

- ^ abcTacke et al. 2015, p. 107.

- ^Lart, Peter. 'Westerlies: Volk's Popular.' Flying magazine, August 1974, p. 82.

- ^'Volksplane VP-1.'Aircraft Spruce and Specialty Co., 2017. Retrieved: August 29, 2017.

- ^'Evans Aircraft Company frequently asked questions.'Evans Aircraft Company, 2017. Retrieved: August 29, 2017.

- ^Stich, Mary. 'Aeronews: Gleaming Volksplane.' Air Progress, August 1973, pp. 22–23.

- ^Mooney, Walt. 'Pilot report: Volksplane.' Air Progress, March 1970, p. 39.

- ^Mooney, Walt. 'Pilot report: Volksplane.' Air Progress, March 1970, pp. 39, 42.

- ^Taylor 1982, p. 542.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bayerl, Robby, Martin Berkemeier et al. World Directory of Leisure Aviation 2011–12. Lancaster UK: WDLA UK, 2011. ISSN1368-485X.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft since 1919, Volume 2. London: Putnam, 1974. ISBN0-370-10010-7.

- Purdy, Don: AeroCrafter – Homebuilt Aircraft Sourcebook, Fifth Edition. Chatswood, New South Wales, Australia: BAI Communications, 1998. ISBN0-9636409-4-1.

- Tacke, Willi, Marino Boric et al. World Directory of Light Aviation 2015–16. Ivry sur Seine, France: Flying Pages Europe SARL, 2015. ISSN1368-485X.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1982–83. London: Jane's Yearbooks, 1982. ISBN0-7106-0748-2.